From Barrel to Glass: How Wine Vessels Shape Flavor, Texture, and Style

Just like the right outfit can change how you feel, the vessel used to ferment and age wine transforms the final result. Whether oak, steel, concrete, or clay, the chosen vessel can shape everything from flavor to structure to longevity.

You’ve swirled, sniffed, and sipped—but have you ever thought about what your wine lived in before it reached your glass? We’ve covered the journey that grapevines take in the vineyard, but what happens next?

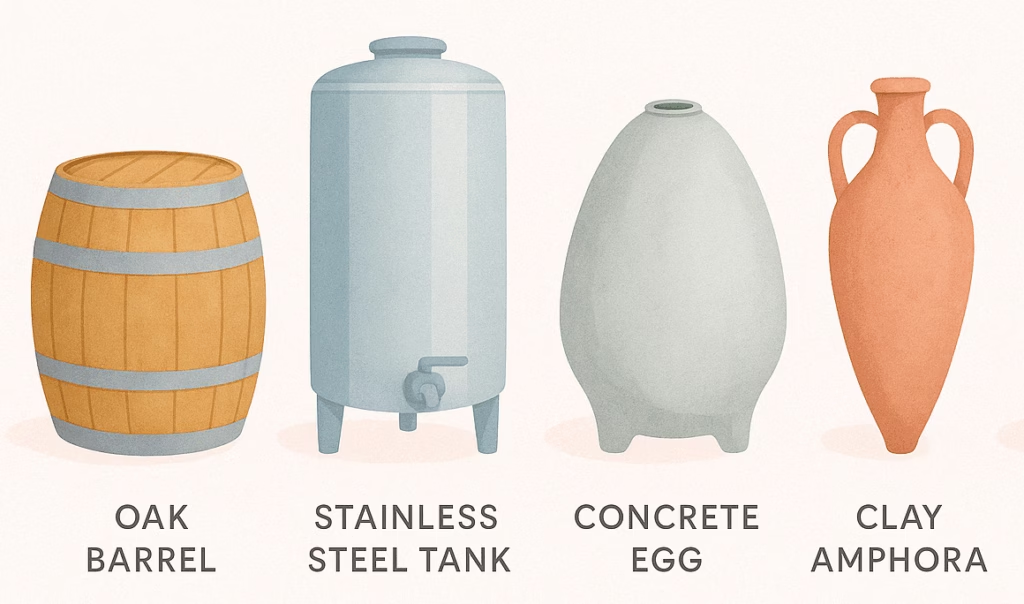

Once the grapes are harvested, pressed, and their juice is ready, the winemaker chooses what kind of vessel to use for fermentation (when yeast converts sugar into alcohol), and sometimes for aging (when the wine develops body, texture, and complexity). Just like the right outfit can change how you feel, the vessel used to ferment and age wine transforms the final result. Whether oak, steel, concrete, or clay, the chosen vessel can shape everything from flavor to structure to longevity.

Let’s uncork the most common wine vessels, what they do, and where you’re likely to encounter each one.

Oak Barrels: The Chic French Girl with a Spicy Edge

She’s effortlessly stylish, owns three trench coats, and has never been late to apéro.

Oak has been a go-to for centuries, used for both fermentation and aging, especially in reds and fuller-bodied whites. It adds structure, spice, and that irresistible whisper of vanilla and toast.

- What Happens Inside: Wine slowly breathes through the porous oak, picking up flavors like vanilla, clove, and smoke. Gentle oxidation softens tannins and rounds out texture.

- Result: Fuller body, deeper color, spiced or toasted notes

- Common Grapes: Chardonnay (Burgundy, Napa), Cabernet Sauvignon (Bordeaux, Napa), Pinot Noir (Oregon), Tempranillo (Rioja)

- Regions: France (subtle French oak), USA (bolder American oak), Spain, Italy, Argentina

Wine notes frequently refer to new oak or neutral oak barrels. New oak (barrels used for the first time) imparts intense flavors—like baking spice, caramel, or coconut—while neutral oak (previously used barrels) softens texture without adding new flavor. You’ll often find new oak in premium Napa Cabs or Rioja Gran Reservas, and neutral oak in Burgundian Pinot Noir or Loire Valley whites where subtlety is key.

The origin of the barrel also matters: French oak is tighter-grained and more elegant, bringing delicate spice and structure. American oak has a looser grain and brings bolder flavors—vanilla, coconut, and even dill—with a toastier vibe. Winemakers choose based on whether they want refined and structured, or bold and plush.

💡 Pro tip: Barrel size matters too. Smaller barrels = more oak influence. Larger, older barrels = more subtle. Foudres (large wooden vats), sometimes used in Loire Valley Chenin Blancs, provide gentle structure without overpowering delicate aromatics.

🥂 Stainless Steel: The California Clean Girl

She’s effortlessly refreshing, always SPF’d, and never misses a farmers market.

Stainless steel is sleek, cool, and completely neutral, which makes it ideal for preserving bright, fruity, and aromatic wines. It’s used mostly during fermentation, though some wines are aged briefly in steel before bottling.

- What Happens Inside: Temperature control allows for a slow, clean fermentation, enhancing zippy acidity and pure fruit. No oxygen means no outside influence.

- Result: Crisp, clean wines with high aromatic lift and juicy freshness

- Common Grapes: Sauvignon Blanc (Marlborough, Loire), Riesling (Mosel), Albariño (Rías Baixas), Vermentino (Italy)

- Regions: Germany, Austria, New Zealand, coastal California

Stainless steel vessels can range from petite 1,000-liter tanks in boutique wineries to towering 50,000-liter behemoths in large-scale cellars. While size doesn’t impact flavor directly, it does affect how precisely a winemaker can control the fermentation process.

Concrete: The Crunchy Coachella Girl

She’s grounded, natural, and always knows which booth has the biodynamic pét-nat.

Concrete vessels—especially egg-shaped tanks—are having a moment, especially with natural and minimal-intervention winemakers. Concrete can be used for both fermentation and aging, offering the purity of steel with the texture-building benefits of oak.

- What Happens Inside: Though neutral in flavor, concrete is slightly porous. It allows gentle oxygen exchange that softens the wine. Egg shapes promote natural circulation, keeping the wine in motion and enriching mouthfeel.

- Result: Creamy texture, minerality, and depth without added flavors

- Common Grapes: Chenin Blanc (Loire, South Africa), Grenache & Syrah (Rhône), Carignan (Chile)

- Regions: France (especially Rhône Valley), Argentina (Malbec), California (natural producers)

Why the egg? The shape keeps the lees (spent yeast cells) suspended, adding creaminess and complexity without oak influence.

Clay Amphorae: The Modern Mystic

She journals by candlelight, follows lunar cycles, and probably makes her own incense.

Dating back over 8,000 years, clay amphorae (also called qvevri in Georgia and tinajas in Spain) are making a comeback with natural winemakers and old-world revivalists. These vessels are used for fermentation and sometimes aging, especially for skin-contact whites and rustic reds.

- What Happens Inside: Amphorae allow slow, natural oxidation and a touch of thermal insulation. Wines often remain on their skins (even whites), developing tannin and texture. Some amphorae are buried underground for temperature control.

- Result: Earthy, grippy wines with mineral complexity and ancient-world soul

- Common Grapes: Rkatsiteli (Georgia), Garnacha (Spain), Malvasia (Italy), Zibibbo (Sicily)

- Regions: Georgia, Italy, Spain, Slovenia, Oregon, California

Amphorae are beloved for skin-contact white wines, creating amber-hued, structured bottles with notes of tea, dried fruit, and spice.

Want to remember what’s in the tank, download my summary PDF for on the go or consult the chart below:

| Vessel | What Happens Inside | Resulting Wine | Common Grapes | Typical Regions |

| Oak Barrels | Micro-oxygenation and flavor infusions | Fuller body, spiced/toasty notes, deeper color | Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Tempranillo | Burgundy, Napa, Bordeaux, Rioja |

| Stainless Steel Vats | Pure neutral environment, no oxygen exchange | Crisp, fresh, aromatic, high acidity | Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, Albariño, Vermentino | Marlborough, Mosel, Rías Baixas, Loire |

| Concrete Eggs | Micro-oxygenation, no added flavors, natural circulation | Creamy texture, added minerality, subtle structure | Chenin Blanc, Grenache, Syrah, Carignan | Loire, Rhône Valley, California, Argentina |

| Clay Amphorae | Slow oxidation, often includes skin contact | Earthy, grippy, complex, oxidative | Rkatsiteli, Garnacha, Malvasia, Zibibbo | Georgia, Sicily, Spain, Oregon |

Final Pour: From Grape to Great

Whether your glass is brimming with a toasty, barrel-aged Chardonnay or a zippy, steel-fermented Albariño, the winemaker’s choice of vessel plays a starring role in the wine’s flavor, texture, and personality.

So next time you take a sip, think about where your wine grew up. Was it coddled in a cozy barrel? Swirled in a concrete egg? Steeped in ancient clay? The vessel is part of the wine’s coming-of-age story—and every sip tells a piece of it.

Cheers to great grapes and the vessels that shape them!